import numpy as np

import matplotlib.pyplot as plt

fig, ax = plt.subplots()

ax.set_xlim(-0.5,2)

ax.set_ylim(-0.5,2)

ax.axhline(0, color='black', linewidth=0.5)

ax.axvline(0, color='black', linewidth=0.5)

ax.quiver(0,0,1,0, color='red', scale=1, scale_units='xy', angles='xy')

ax.quiver(0,0,0,1, color='red', scale=1, scale_units='xy', angles='xy')

ax.text(1.1,0, '$u_1$', color='red', fontsize=12)

ax.text(0,1.1, '$u_2$', color='red', fontsize=12)

ax.set_aspect('equal')

plt.grid(True)

plt.gca().set_facecolor('#f4f4f4')

plt.gcf().patch.set_facecolor('#f4f4f4')

plt.show()Dimensionality Reduction: Principle Component Analysis (PCA)

Introduction

Principal Component Analysis (PCA) is a powerful technique used in machine learning and statistics for unsupervised dimensionality reduction. It transforms high-dimensional data into a lower-dimensional form while preserving the most important features or “components” of the data. This is particularly useful when dealing with large datasets that are difficult to visualize or computationally expensive to process.

For example, if we have a dataset that contains a lot of images of 20x20 pixels and we convert the images to one dimensional vectors then there are total 400 features which makes the analysis harder. PCA finds a low (best \(d\)) dimensional subspace approximation that minimizes the least square error

What is Principal Component Analysis (PCA)?

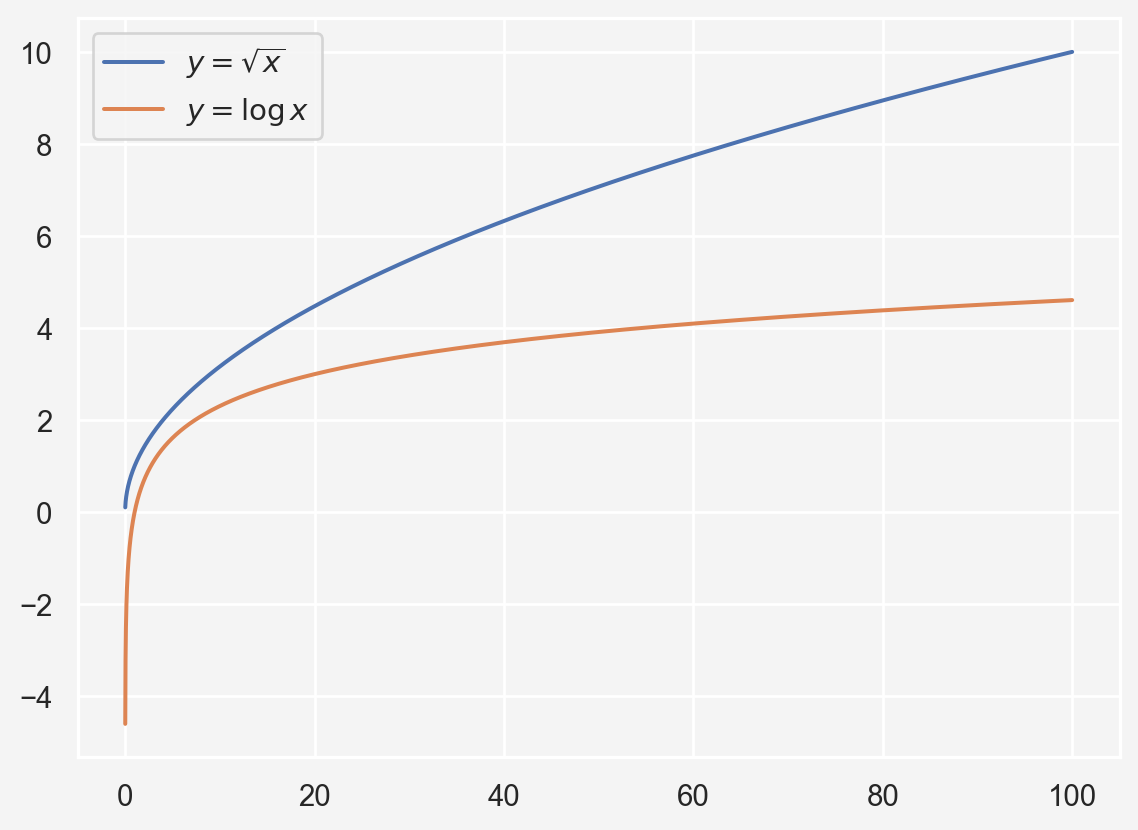

Let’s start from the beginning. If we have a set of orthogonal basis vectors say \(\mathbf{u}=(u_1,u_2,\dots, u_p)\) then \(u_i^Tu_j=\delta_{ij}\) for \(1\le i,j \le m\). For example, consider \(u_1=\begin{bmatrix}1\\ 0\end{bmatrix}\) and \(u_2=\begin{bmatrix}0\\1\end{bmatrix}\)

\[\begin{align*} u_1^Tu_2 & = \begin{bmatrix}1 & 0\end{bmatrix} \begin{bmatrix}0\\1\end{bmatrix} = 0 \hspace{4mm}\text{and}\hspace{4mm} u_2^Tu_1 = \begin{bmatrix}0 & 1\end{bmatrix}\begin{bmatrix}1 \\ 0\end{bmatrix}=0\\ u_1^Tu_1 & = \begin{bmatrix}1 & 0\end{bmatrix} \begin{bmatrix}1\\0\end{bmatrix} = 1 \hspace{4mm}\text{and}\hspace{4mm} u_2^Tu_2 = \begin{bmatrix}0 & 1\end{bmatrix}\begin{bmatrix}0 \\ 1\end{bmatrix}=1 \end{align*}\]

Now suppose we have a data set \(X\) with columns are features and \(k\)th observation \(x^{(k)}=(x_1^{(k)},x_2^{(k)},\dots,x_p^{(k)})^T\). Now let \(\mu=\bar{x}= \frac{1}{n}\sum_{k=1}^{n}x^k\), that is for \[\begin{align*} X & = \begin{bmatrix}x_{11}&x_{12}&\dots x_{1p} \\x_{21}&x_{22}&\dots x_{2p} \\ \vdots & \vdots &\ddots \vdots \\x_{n1}&x_{n2}&\dots x_{np} \end{bmatrix}\\ \mu_j &= \frac{1}{n} \sum_{i=1}^{n} x_{ij}\\ \mu & =\begin{bmatrix}\mu_1\\ \mu_2 \\ \vdots\\ \mu_p\end{bmatrix} = \frac{1}{n} \sum_{i=1}^{n} X^i \end{align*}\]

Now with the orthogonal vectors, we can write \[ x^k-\mu = \sum_{i=1}^{p}\left[(x^k-\mu)\cdot u_i\right]u_i = \sum_{i=1}^{p} a_i^k u_i\]

In PCA, we aim to find \((u_1,u_2,\dots, u_d)\) that minimizes the reconstruction error, defined as the squared distance between each data point \(x^k\) and its projection onto the subspace spanned by the top \(d\) principle components: \[\mathbf{E}(u_1,u_2,\dots, u_d)=\sum_{k=1}^{n}\left\|x^k -\left(\mu+\sum_{i=1}^{d} a_i^k u_i\right)\right\|^2\]

Here \(\sum_{i=1}^{d} a_i^ku_i\) is the projection of \(x^k\) onto the subspace spanned by the top \(d\) dimensional components. The term inside the norm, \(x^k -\left(\mu+\sum_{i=1}^{d} a_i^k u_i\right)\), represents the residual error after projecting \(x^k\) onto this subspace. The goal is to minimize this error.

The residual variance corresponds to the directions (or principal components) not captured by the top \(d\) principal components. Specifically, these are the components corresponding to \(u_{d+1}, \dots, u_p\), where \(p\) is the total number of features (or components).

Now, the norm inside the error function can be decomposed as follows:

\[ x^k - \left( \bar{x} + \sum_{i=1}^{d} a_i^k u_i \right) = \left( x^k - \bar{x} \right) - \sum_{i=1}^{d} a_i^k u_i \]

We define \(z^k = x^k - \bar{x}\), so the error becomes:

\[ E(u_1, \dots, u_d) = \sum_{k=1}^{n} \left\| z^k - \sum_{i=1}^{d} a_i^k u_i \right\|^2 \]

The key idea here is that \(z^k\) is a vector in the original \(p\)-dimensional space, and we are approximating it by projecting it onto the top \(d\)-dimensional subspace spanned by \(u_1, \dots, u_d\).

Since \(u_1, \dots, u_p\) form an orthogonal basis, \(z^k\) can be completely expressed in terms of all the basis vectors \(u_1, \dots, u_p\). In particular:

\[ z^k = \sum_{i=1}^{p} a_i^k u_i \]

where \(a_i^k = z^k \cdot u_i\) are the projections of \(z^k\) onto each basis vector \(u_i\). Therefore, the reconstruction error \(E(u_1, \dots, u_d)\) is the squared norm of the residual part of \(z^k\) that is not captured by the top \(d\) principal components:

\[ E(u_1, \dots, u_d) = \sum_{k=1}^{n} \sum_{i=d+1}^{M} (a_i^k)^2 \]

This means that the error comes from the projection of \(z^k\) onto the remaining \(p-d\) principal components, i.e., \(u_{d+1}, \dots, u_p\). Thus,

\[\begin{align*} E(\mathbf{u}) & = \sum_{k=1}^{n} \left\|\sum_{i=d+1}^{p}(z^k\cdot u_i)u_i\right\|^2\\ & = \sum_{k=1}^{n}\sum_{i=d+1}^{p} \left(z^k\cdot u_i\right)^2 \end{align*}\]

We start with the dot product \(z^k \cdot u_i\), which is just a scalar:

\[ z^k \cdot u_i = (z^k)^T u_i \]

This is simply the sum of the element-wise products of \(z^k\) and \(u_i\): \[\begin{align*} z^k \cdot u_i &= \sum_{j=1}^{M} z_j^k u_{ij}\\ \implies (z^k \cdot u_i)^2 &= \left( \sum_{j=1}^{M} z_j^k u_{ij} \right)^2 \implies \left( \sum_{j=1}^{M} z_j^k u_{ij} \right)^2 &= \sum_{j=1}^{M} \sum_{l=1}^{M} z_j^k z_l^k u_{ij} u_{il} \end{align*}\]

Notice that we can rewrite the product \(z_j^k z_l^k\) as an outer product of the vector \(z^k\) with itself:

\[ z^k z^{kT} \]

The outer product \(z^k z^{kT}\) is a matrix, specifically an \(p \times p\) matrix. Each element of this matrix at position \((j, l)\) is \(z_j^k z_l^k\), exactly what we have in the double sum.

So, instead of writing out all the sums explicitly, we can represent the whole thing as a matrix:

\[ (z^k \cdot u_i)^2 = u_i^T (z^k z^{kT}) u_i \]

This is called a quadratic form. So,

\[\begin{align*} E(\mathbf{u}) & = \sum_{k=1}^{n} \left\|\sum_{i=d+1}^{p}(z^k\cdot u_i)u_i\right\|^2\\ & = \sum_{k=1}^{n}\sum_{i=d+1}^{p} \left(z^k\cdot u_i\right)^2 \\ & = \sum_{k=1}^{n}\sum_{i=d+1}^{p} u_i^Tz^kz^{kT}u_i \\ & = \sum_{i=d+1}^{p} u_i^T\Sigma u_i \\ \end{align*}\]

where,

- \(\Sigma = \sum_{k=1}^{n}(x^k-\mu)(x^k-\mu)^T=X^TX\)

- \(X=(x^1-\mu, x^2-\mu,\dots,x^p-\mu)^T\)

So now we have \[E(\mathbf{u})=\sum_{i=d+1}^{p} u_i^T\Sigma u_i \]

and \(E(\mathbf{u})\) is minimized when \(u_i\)’s are the eigenvectors of \(\Sigma\). Then

\[E(\mathbf{u})=\sum_{i=d+1}^{p} u_i^T\lambda_i u_i =\sum_{i=d+1}^{p} \lambda_i \]

and we get our desired \(u_{d+1},\dots, u_{p}\) components that minimizes the projection error. So if we take the first \(d\) of these correspond to the \(d\)-largest eigenvalues we get the principle components.

Long story short

- We have \(n\) data points with \(p\) column vectors \(x^1,x^2,\dots,x^p\)

- We compute the mean \(\mu= \frac{1}{n}\sum_{k=1}^{n}x^k\)

- Then we compute the matrix \(X=(x^1-\mu, x^2-\mu,\dots,x^p-\mu)^T\)

- Next, compute the eigenvalues of \(\Sigma = \sum_{k=1}^{n}(x^k-\mu)(x^k-\mu)^T=X^TX\) and short them in decreasing order

- Choose \(d\), the number of principle components

- Then we get the principle components \(P=[v_1,v_2,\dots, v_d]_{p\times d}\)

- To project any column vector \(z\), we compute \(projection(z)=P^T(z-\mu)\)

Benefits of PCA

- Dimensionality Reduction: PCA can reduce the number of variables, which speeds up algorithms and makes models more interpretable.

- Visualization: PCA is often used to project high-dimensional data into 2D or 3D for visualization.

- Noise Reduction: By focusing on the principal components, PCA can eliminate irrelevant noise in the data.

- Avoid Multicollinearity: PCA removes multicollinearity by creating uncorrelated principal components.

Limitations of PCA

- Linear Assumption: PCA assumes linear relationships between features. Non-linear patterns in data are not captured well by PCA.

- Interpretability: While PCA can simplify data, the new components may not be easily interpretable.

- Loss of Information: Reducing dimensions might result in the loss of some information or variance, depending on how many components are retained.

PCA in Python: Implementation and Visualization

Now that we understand the theory behind PCA, let’s implement it in Python using the sklearn library and visualize the results.

import numpy as np

import pandas as pd

import matplotlib.pyplot as plt

from sklearn.decomposition import PCA

from sklearn.preprocessing import StandardScaler

from sklearn.datasets import load_irisFor this example, we will use the famous Iris dataset, which contains 4 features (sepal length, sepal width, petal length, and petal width) of 3 species of iris flowers.

# Load the Iris dataset

iris = load_iris()

X = iris.data

y = iris.target

# Standardize the data

scaler = StandardScaler()

X_scaled = scaler.fit_transform(X)We will reduce the data from 4 dimensions to 2 for visualization.

pca = PCA(n_components=2)

X_pca = pca.fit_transform(X_scaled)

print(f"Explained Variance Ratio: {pca.explained_variance_ratio_}")Explained Variance Ratio: [0.72962445 0.22850762]The explained variance ratio shows how much variance each principal component captures. In many cases, the first two components capture most of the variance.

Let’s plot the Iris dataset using the first two principal components.

plt.figure(figsize=(8, 6))

colors = ['red', 'blue', 'green']

for i, color in enumerate(colors):

plt.scatter(X_pca[y == i, 0], X_pca[y == i, 1], label=iris.target_names[i], color=color)

plt.title('PCA of Iris Dataset')

plt.xlabel('Principal Component 1')

plt.ylabel('Principal Component 2')

plt.legend()

plt.grid(True)

plt.savefig('pca.png')

plt.gca().set_facecolor('#f4f4f4')

plt.gcf().patch.set_facecolor('#f4f4f4')

plt.show()The plot shows the data projected onto the first two principal components. We can observe how the three species cluster in the reduced 2D space. This visualization helps us see the separability of the classes using only two dimensions, instead of four.

References

- Jolliffe, I. T. (2002). Principal Component Analysis. Springer Series in Statistics.

- The seminal book on PCA, providing an in-depth theoretical background.

- Shlens, J. (2014). A tutorial on principal component analysis. arXiv preprint arXiv:1404.1100.

- An excellent tutorial that breaks down PCA concepts with clear mathematical derivations.

- Bishop, C. M. (2006). Pattern Recognition and Machine Learning. Springer.

- This book offers a comprehensive guide to PCA and other machine learning techniques.

- Hastie, T., Tibshirani, R., & Friedman, J. (2009). The Elements of Statistical Learning. Springer.

- Covers PCA as well as a variety of other machine learning and statistical techniques.

- Géron, A. (2019). Hands-On Machine Learning with Scikit-Learn, Keras, and TensorFlow. O’Reilly Media.

- A practical guide with hands-on code examples, including PCA implementation in Python.

Share on

You may also like

Citation

@online{islam2024,

author = {Islam, Rafiq},

title = {Dimensionality {Reduction:} {Principle} {Component}

{Analysis} {(PCA)}},

date = {2024-09-24},

url = {https://mrislambd.github.io/dsandml/pca/},

langid = {en}

}